“If only the anti-federalist way of thinking had won out…” That is what a conservative said to me recently – a response to an episode of The Presidential Pod that I posted earlier in the year about Thomas Jefferson. It struck me as a bit odd of a comment for various reasons. It also left me really digging into the connections between the founding factions and modern parties. An interesting thing starts to emerge upon close inspection: an inconsistency of “the right” between its political ideology and its style of governance.

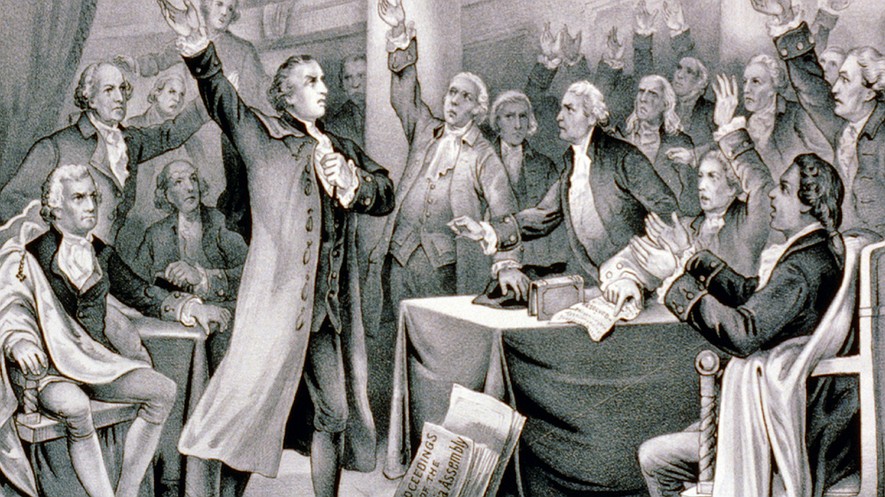

If we were to trace the lineage of the modern conservative Republican party to its American origins, we would find it in the anti-federalists: the party of Jefferson, James Madison, George Clinton, and Patrick Henry. This political faction emerged to essentially fight the idea of a central government with any power. Ultimately espousing the virtues of “small government” with practically no real authority – never mind less – this would be the rallying cry of the right’s beliefs.

It would be worth pointing out some key differences between the modern conservative movement and the anti-federalists. Where today, conservatives herald the constitution as if it were the word of God, many anti-federalists were opposed to it. It’s a funny thing to consider today, but at the time, the constitution was hugely controversial. For starters, it was a secret, borderline illegal meeting of a select few to completely overhaul the government structure without public knowledge. Plus, it introduced the concept of the President, which many anti-federalists felt would lay the groundwork for an American king. It also added several elements of monarch power, such as the presidential pardon or eminent domain. The former was an inherent power granted to the individual considered supreme ruler of a region. The latter stems from the concept that all the land truly belongs to the king, while the citizens merely occupy it. (And, indeed, many Southern anti-federalists worried it would pave the way to a federal government that could dictate whether it were legal to own slaves. That was a big reason why the slavery debate got tabled until after 1800.)

Another intriguing way that the modern conservative ideology has shifted is in its obsession with the military. It stands to reason a professional standing military would be necessary for the defense of a nation. One needs only read a little of the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812 to recognize how poorly equipped America was for its own defense. A nation of the citizen-farmer militiaman proved absurdly unreliable. Indeed, in the War of 1812, it was the Navy – a branch that required a certain amount of service for training – that kept the country from complete disaster, while the militias and ground war largely went nowhere and struggled to organize adequate defense against the invading British. Mix all that in with Congress being completely unable to pay for war since they couldn’t levy taxes to fund it. In fact, defaulting on loans and the economic decimation it was causing is a huge reason why both President James Madison and Secretary of State James Monroe – two of the most prominent to emerge from the anti-federalist vein – defied classical republican ideology to support a national bank.

The rub with standing armies is that it was feared to be a tool of the monarch. The argument went that professional militaries represented the people in power, not the citizenry. The British invaded, for example, not because their soldiers wanted to, but because they were ordered to by a king using the military to police his disagreeable subjects. Concern about a professional military in times of peace stemmed from the fear that the government would use it against its own population. The early anti-federalists were fans of classical republican virtues seen in Rome, and they were aware that Rome changed from a republic to an empire in tandem with a growing standing army. (The other thought was that a professional army would separate civic virtue among the populations, as people would no longer feel the defense of their nation was up to them specifically.) On some level, these concerns were well placed. American history is full of moments in which the military (or, in modern times, militarized police force) have been called in to suppress protests.

Most people across the political spectrum would agree that a standing military in times of peace are necessary. It is funny, then, that it is the anti-government conservative right that constantly argues for greater military power and a more militarized police force, while the pro-government liberal left wants less. How, then, does the “less government authority” party argue for stronger government tools to enforce stronger government powers and edicts? It is telling that the original Republican party, that of Madison and Jefferson, actually kept cutting the military budget under President James Monroe (a man who was arguably more anti-federalist than Madison before him, and possibly even Jefferson).

The ultimate problem for the conservative right is that it cannot reconcile its campaign rhetoric with its power and responsibility to govern when elected. To be perfectly clear, this isn’t about inconsistencies of particular issues. Lord knows everyone has them. The argument here isn’t pointing out the inconsistency of the right demanding unfettered access to guns because it “protects us from government tyranny,” while turning around at the very same time to argue that we need to give the government more guns themselves. (Seriously, who do they think is going to kick down their doors and take their guns by force if the government wants to? Their district attorney or state legislator? No. It’s going to be the police or the army – agents of the government.)

This isn’t meant to ignore per issue inconsistencies from the left either. For example, how many are fighting for a $15 an hour minimum wage while then turning around to complain at how expensive things have gotten (or advocating racial and economic justice who then turn around to complain about low-income housing in their neighborhood). This specific post is discussing the ideological inconsistency as it pertains to governance. Put bluntly, the Republicans want smaller government, more accountability, less spending, and less government authority…until they’re in power and then they don’t.

To be sure, liberal democrats have no shortage of hypocrisies as well, but on a fundamental basis regarding the role of government, they are consistent. Consider this a three-pronged question. What is the role of government? What does it need to fulfill that role? What will I do to make sure that happens, if I were charged with governing? For the left, they believe in the government as a possible solution to problems. As a result, they believe the government should have certain powers – and may even feel they need more – to solve those public problems. Finally, when they are elected, they will use those powers to try and solve those public problems. Now, how they go about that might be short-sighted or problematic itself. The point, again, is to just note the consistency in ideology as it applies to governance. They believe in government. They use government.

Comparatively, conservative Republicans flow like this: government is not a solution to most problems. As a result, they believe the government should not have powers – and may even feel they need fewer powers than currently allotted. Finally, when they are elected and are in government positions, they…use that power to enact any policy they want anyway. There is a fundamental inconsistency in advocating less federal authority while also advocating a federal law banning same-sex marriages or adoptions. There is a fundamental inconsistency with arguing the government has no business telling you what to do with your business, while also supporting a government that will force women to jump through countless hoops to get access to necessary health care. There is a fundamental inconsistency with wanting fiscal responsibility as it pertains to welfare, but then supporting one of the most wasteful ideas in American history in the border wall. There is a fundamental inconsistency with arguing we need guns to protect us from government abuse, while also ramping up the militarization of law enforcement to suppress public protest over perceived government abuses. In every case, the right is essentially arguing for “smaller government,” except when they themselves personally care about something. In that case, they’re all for the government having those powers and that authority.

It is easy to think of this as a hypocrisy that has emerged over time, from the anti-federalists to the Democratic-Republicans to the Democrats of the post-Civil War up to the mid-20th century, to the modern Republicans. That isn’t quite accurate, though. The parties formed from the likes of John Calhoun and George Mason have always been against something until they were for it (usually because they were in power). Patrick Henry, in an effort to shut out the pro-Constitution James Madison, used his power as governor to re-draw the districts, effectively attempting to undemocratically block Madison from winning a seat in the Senate. It’s hard to imagine Henry being particularly cool with the idea if the roles had been reversed, and it was the pro-Constitution Madison using government powers granted to him to block him. It’s just the same as how hard it is to imagine any modern Republican being cool with even a quarter of the stuff the current President and his staff have done or been involved with if it were President Obama or any other democrat in office. They’re against it, until they have power, and then they’re for it.

When you look at the roots of this party, this is nothing new. Consider how, during the election of 1800, Democratic-Republicans were literally preparing for an armed revolt if Thomas Jefferson did not win the election in the House of Representatives. James Monroe expanded the standing military – a thing he chastised Washington and Adams for doing. He was surprisingly open with the opinion that he didn’t “trust” Federalists with a military, which is how he argued he was not being logically inconsistent. There has always been this “my way or bust” from conservatives – a sense that “they” shouldn’t have that power, but “we” should. And sure, it’s not like the left doesn’t have its share of similar people. Alexander Hamilton is a notorious example of someone who would find ways to sabotage members of his own faction if they did not fully support his agenda. Thomas Pickering, a supporter of Hamilton himself, would do the same thing. And certainly, you can look at George Washington or John Adams who often unfairly chastised democratic-republicans in their administration, largely because they incorrectly believed those individuals may have been trying to undermine them. (This, of course, was a true scenario as it pertained to Jefferson within the Washington and Adams administrations, but was less true as it pertained to Monroe in the Adams administration.) As it pertains to more modern history, liberal democrats have been a key player in expanding executive authority – the type we now are second-guessing with a literal psychopath in office.

Now, I’m definitely what you would call a leftist, and I believe in the idea that government can be a solution to problems. Subsequently, I believe it should have powers to accomplish those goals. Not infinite powers, of course. There still needs to be limitations on what the government can do, for many reasons. That said, there is no question that – with maybe the likes of Hamilton and Pickering aside – the bulk of the founders would be shocked at the size and scale of our governments. Part of this has been political gain for factions – everyone across the political spectrum has jumped at grabbing power so they can sustain it and dictate policy. Part of it has also been the sheer size and expansion of the United States. Early American conservatives were fans of Rome, a republic that thrived in large part due to its relatively small city-state nature. There was always going to be a question of how sustainable a republic would be for a country that continued to increase its size exponentially. The entire reason for the Constitutional Convention was that the country had become too big and populated for a Confederation to continue to be successful. (Indeed, we don’t often discuss how unstable the country was, and how many mini-wars nearly erupted among states between 1783 and 1789.) There is just no way for that “original vision” of a small republic to exist as the nation continued to expand across an entire continent. But surely, even Washington, Adams, and Hamilton might be shocked to see what our government has become.

At the same time, I’m struck by that logic that the ultimate problem with the United States is that the “Federalists won.” This is a confusing argument because it ignores that over the span of 40 years after the first three presidential terms, the conservative Democratic-Republican party had a stranglehold on political power in Congress and the executive branch. Every President from 1800 to 1841 was a Democratic-Republican or Democrat, with most coming from the South, where anti-federalist ideology was often strongest. Even Presidents of the Whig party, with some notable ties to Federalist thinking, ultimately emerged out of the Democratic-Republican party.

Consider that it wasn’t Federalists who outlawed the importation of slaves in 1806. It wasn’t Federalists who were trying to upset the balance of north/south political power with expansion and government protection. Additionally, Madison and Monroe practically reversed several key tenants of anti-federalist thought in their presidencies by expanding the navy and army, increasing the foreign ministry and subsequently getting more involved in foreign affairs, created a new national bank, issued tariffs to protect mercantilism over agriculture, increased national debt, advocated public funds for interior improvements, and used a loose construction of the constitution to wage their military efforts. Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, and Jackson all used secrecy and excess of authority to influence the affairs of foreign, sovereign nation. Jefferson tried to instigate a revolt for a more US-friendly leader in Tripoli, Never mind the shenanigans Madison, Monroe, and Jackson all got up to in Florida. (Which begs the question of, when was the United States ever truly “isolationist”?)

Jefferson is often considered the patron saint of small government, and in many areas, he certainly did shrink it from the previous Federalist administrations. At the same time, he issued unpopular tariffs that his southern compatriots found excessive. It is telling, as well, that while he shrank the scope of the Alien & Sedition Acts, he did not abandon them completely. (Aspects of those are still in effect today.) More importantly, and more to my larger point, he acted to purchase the Louisiana Territory knowing that he didn’t know if he had the authority to do so. By today’s standards, it’s hard to argue that a similar move would be unconstitutional; at the time, it was actually pretty controversial. The fact is, he was so unsure if he had the power to do what he did that he offered to resign once it was clear Congress couldn’t undo it. This is the perfect example of conservative philosophy towards governance: “No one should have this power, until I have this power and see a need to use it.” Or, to put another way, “I am against government…until I have to govern.”

This isn’t calling Jefferson’s leadership into question. Purchasing Louisiana, especially for the price negotiated, was too big a deal for the future defense and prosperity of the nation. The point, however, is that Jefferson – as the leader of the country, charged with governing – saw an opportunity to improve the nation, and jumped on it. He used his own authority, one he didn’t actually know he had, to act. Consider that this was the same man who, not even a decade earlier, had worked to undermine President Washington who – similarly – declared neutrality in the growing feud between Britain and France, recognizing the US was too fragile to start another fight. One can only imagine the outrage of Jefferson, should it have been John Adams to potentially exceed his authority to purchase Louisiana. (It took decades before Jefferson reluctantly gave Adams even a modicum of credit for developing the Navy, which was hugely significant in the War of 1812.)

Madison was faced with even more problems during his tenure in office. His two terms saw substantial issues that were only solvable through a change in course. If Madison had stuck with the anti-federalist agenda, it is hard to imagine the nation staying together much longer. The creation of a standing military and national bank came out of seeing how lacking those dramatically harmed the country. The expansion of a foreign ministry was done out of recognizing how – in a time of global trade (yes, America has always relied on global trading partners) – there was a need to strengthen diplomatic ties across the world so as to protect those interests. The desire to improve the interior came from seeing how poorly developed the nation really was, and how that hurt defense efforts in the war.

This trend of recognizing the value of governance from traditionally anti-federalist followers continued throughout the Era of Good Feelings. Monroe expanded the military further, despite his conservative Congress cutting the defense budget. More, he unilaterally decreed that the United States would not tolerate any European powers interfering in the Western Hemisphere (popular known as the Monroe Doctrine, but don’t sleep on John Quincy Adams’s role in it). This effectively forced America to become a bigger international player. The war hero Andrew Jackson would so often strong arm his way to his goals that he both ignored the President when he led a campaign in Florida, and then later prepared the government’s army to suppress Southern protest over the Nullification question (read: a Southern Democratic-Republican was prepared to use the standing army to squash the dissent of Southern “state’s rights” protesters – why, again, do so many conservative Republicans demand he stay on the $20?)

And so, here we are: a modern Republican party espousing virtues of “small government” and “less government authority” who have given us things like the Patriot Act and are trying to abuse their Congressional powers (often breaking them) to take away health care from millions of Americans. We see the “more responsibility” Republicans acting completely hypocritical, seemingly without consequences, doing exactly the things they complain about a Democratic Congress doing. We see the “less government” Republicans using government authority to seize private lands for the sake of the border wall, who are also trying to cut interior improvement funding so they can fund the border wall. These are the same Republicans that keep saying they have to take away our health care because “people voted for us and we campaigned on the promise” who also keep re-drawing district lines to ensure they keep getting elected. These are the same Republicans telling us same-sex marriage should be up to the states, who then will push a federal law banning it nation-wide.

But make no mistake: this is the same party that argued “state’s rights” just after the Civil War, who also took away the Confederate states’ rights to ever decide for themselves if slavery could be outlawed (the Confederacy’s constitution itself specifically required all states to, regardless of their will, allow slavery). This is the same party that was against the very existence of the President, who used Presidential authority to purchase Louisiana or get involved in military efforts around the continent and, later, the world.

When you look at the modern Republican party and also read about American history, you can’t help but notice a trend. Conservatives have always been against government until they are government. They have always been against government power until they have government power. It has never been about anything ideological in nature. It has always been about believing they are the only ones who know what’s best. It’s how Jefferson and Monroe could criticize the President acting unilaterally, but then once in the role themselves, acted unilaterally too. This highlights a strange hypocrisy in perspectives. How did the aristocratic elitism of Jefferson, Madison, and the Southern anti-federalist come to resonate with the “average American” to launch the Second Revolution? There has always been, in most ways, a disconnect between what the right has represented with what it has largely been in reality.

It isn’t that the “anti-federalist way of thinking” lost out. It’s that the anti-federalist way of thinking was never an actual, practical belief system in the first place. It is much easier to campaign on the notion of shrinking government authority. It’s a lot harder to do that when you are elected to govern and people expect you to fix problems. Turns out, it’s easier to solve problems when you have powers to address it.

One comment